Blog

IPCC warns world must reach zero GHG emissions by 2075 — Electric Vehicles will play a crucial role

October 17, 2018

Post Author

Did you know the first electric car was developed in 1890 by William Morrison in Iowa? In 1898, Porsche released its own electric car, and by 1900, New York City had a fleet of more than 60 electric taxis! But without available widespread electricity across rural America, the internal combustion engine (ICE) car proceeded to eliminate the demand for electric cars by the 1930s.

Fast forward through two world wars, the advent of rock and roll, and 15 U.S. presidents to 2018. And what do we have to show for the last 120+ years since William Morrison’s first electric car? Well, in addition to all the rest of it, we’re grappling with the dangerous effects of climate change, from more dramatic weather events like floods and fires to coastal flooding.

On October 6th, The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a special report for policy makers with an urgent message: in order to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change, like widespread food and economic insecurity, we must reduce our GHG emissions 45% by 2030 and reach zero emissions by 2075.

Okay, so what exactly does that mean? Well first of all, 2030 is less than 12 years away. For comparison, a new U.S. Senator will have served a mere two terms by the time we need to cut emissions by 45%. How in the world are we ever going to get there? As the leading contributor of GHG emissions, the transportation sector should no doubt garner much of the attention. Electric vehicles will serve as a critical component of the clean energy transition.

On average, one ICE vehicle emits about 10,000 pounds of carbon dioxide per year. Battery electric vehicles don’t have tailpipe emissions, and as electricity becomes increasingly renewable, the environmental and health benefits of driving an EV will only further increase. According to a study by the Union of Concerned Scientists, gas-powered cars emit almost twice as much greenhouse gases than the equivalent electric car over their lifetimes. EVs are also better for our health, emitting less SOx, NOx, and other harmful air pollution that pose a threat to our quality of life.

So what is holding back the inevitable transition to an electric vehicle future? Well that’s like asking why rain isn’t falling from that dark cloud in the sky: the rain will come, it’s just a matter of force. Electric vehicles suffer from a perceived lack of charging infrastructure. I’m sure folks living in New York in 1900 would have scoffed at our modern day range anxiety — electricity was not nearly as widespread as it is today. Nevertheless, we need to make charging easier than spilling gasoline on your shoe at a Conoco. That means ensuring charging is accessible and amenable to every kind of driver and every kind of urban and rural resident.

Some drivers commute 100 miles a day on major highway corridors while others only need to go a few miles a day to drop their kids at school and pick up groceries. Some residents live in single-family homes with garages and electrical outlets to spare while others live in 20-story apartment buildings without dedicated parking spots, much less a place to plug-in their car. For the highway drivers, fast chargers along major corridors are crucial, while city-dwellers only need access to Level 1 or Level 2 chargers a few hours a day. This means developing various kinds of infrastructure, like the peer-to-peer reservable charging network from the startup EVmatch, so we can make electric vehicles more convenient than ICE vehicles.

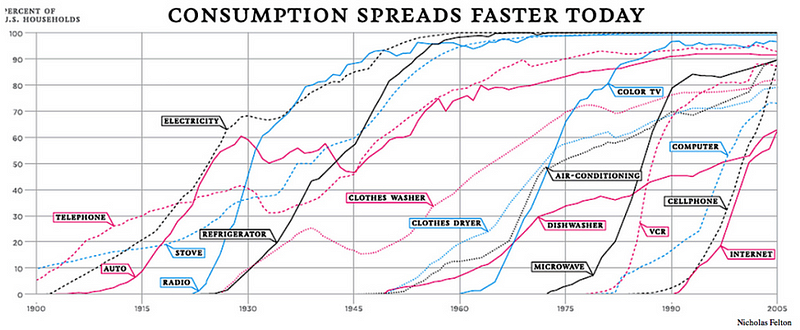

Oh and what about their cost, you ask? The Nissan Leaf, Chevy Bolt, and half a dozen other EV models are already in the $23,000 — $36,000 price range for new vehicles, even before you apply available tax credits and local rebates like the $7,500 federal tax credit. And like all technologies, market competition and economies of scales will drive EV prices down further in the coming years. Just look at Tony Seba’s adoption curves if you’re still skeptical.

We’ve made leaps and bounds in EV technology, resulting in electric vehicles that William Morrison could only dream of in 1890. But he wasn’t facing impending catastrophe and he certainly didn’t have Elon Musk-level fame. We happen to have both in 2018, and with just 12 years before we must cut nearly half our current-day emissions, the time is ripe to listen to the IPCC and get more regenerative brakes on the road.